Invigorating Watercress

By Audrey Stallsmith

"You don't eat 'em," returned Mr Pumblechook, sighing and nodding his head several times, as if he might have expected that, and as if abstinence from watercresses were consistent with my downfall.

As kids, my siblings and I used "looking for watercress" as an excuse to poke around crumbled springhouses. Who knew what treasures of rusting tinware or broken pottery we might unearth?

Besides, it was great fun to perch on the moss-covered, rectangular rocks and dangle fingers or toes briefly in the numbingly cold water. With its tangy taste and array of health benefits, the cress that flourishes in such frigid conditions might be considered similarly bracing!

Its official name, Nasturtium officinale, derives from the Latin nasus tortus ("twisted nose")--a natural reaction to the plant's peppery odor and flavor! It has also been known as roripa or Radicula nasturtium aquaticum. Roripa may come from roro ("to be moist") and ripa ("riverbank"), and radicula indicates "small roots." Aquaticum means "growing in or near water." In Old England, cress was originally pronounced as kers or cerse and considered poor man's food, which explains the phrase "not worse a curse."

Despite its name, there is, Pamela Jones reports in Just Weeds, "no truth in the rumor that Nasturtium officinale is in any way related to the garden nasturtium, whose botanical name is actually Tropaeolum majus. The fact that Tropaeolum majus is also popularly known as Indian cress, although it is not a cress at all, is strictly a coincidence. And the fact that it happens to be equally pungent and wholesome as watercress merely proves that a plant does not have to be a cress to taste like one."

Although Jones assumes John Gerard's flos cuculi ("cuckoo flower") was watercress, the sixteenth-century herbalist actually refers to cuckoo flower as Nasturtium aquaticum minus or "lesser water cress." Among its nicknames, he includes cardamine and lady-smockes. So I would guess that flos cuculi was actually Cardamine pratensis, sometimes also known as "meadow cress."

British street vendors once sold watercress in bunches, and their customers most frequently consumed it in a sandwich for breakfast. In England's milder climate, the plant is considered to be at its best "during any month with an R in it." Here, it would be covered with ice and snow during much of that time, and would probably be a bit small to harvest even in March. So the cress season in PA generally covers the late spring and late fall months.

Because it prefers cold, clear water, the green is most often found in creeks, especially near the sites of the old springhouses I mentioned earlier. (Those small structures generally contained a "trough" of icy spring water, in which crocks of milk or other perishables were set before the days of refrigeration.) Planted just outside those "houses" by the early settlers who knew its value as a spring tonic, watercress helped prevent scurvy-back in the days when it was virtually impossible to find fresh fruit or vegetables during the winter months.

According to Jones, besides Vitamin C, watercress is rich in iron, calcium, copper, potassium, and magnesium, as well as Vitamins A, B2, D, E. Like many other sulfur-containing plants, it also fights cancer.

Perhaps due to its Vitamin C content, watercress and watercress tea are recommended in James Duke's The Green Pharmacy for alleviating colds and gingivitis. Duke relates that, back in the 1800's, Chinese workers on the San Francisco railroad also discovered the plant was helpful in treating tuberculosis.

In China, John Heinerman reports in his Encyclopedia of Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs, it is used in soups to relieve mouth problems such as canker sores. He suggests watercress also be steeped in vinegar and applied with a cloth to the forehead to soothe headaches.

In Herbal Medicine, Dian Dincin Buchman asserts that watercress will "counteract postparty fatigue and alcoholic fumes" and that it "is also useful to offset the smell and taste of smoking." Scientists have discovered that the PEITC in watercress may also help offset the carcinogens in tobacco.

The ancients knew the plant was good for them, even if they didn't know why! Hippocrates supposedly constructed his hospital near a stream, so he could get his hands on watercress whenever he needed it. The plant was often fed to slaves and soldiers to increase their stamina and so came to stand, in the Language of Flowers, for "stability and power." The Greeks thought it sharpened the wits, and many cultures considered it an aphrodisiac.

Watercress lends a bit of zing to spring salads and sandwiches too, and makes a perky garnish for other foods. And, perhaps most revitalizing of all, it will give us adults an excellent excuse to go play in the creek again!

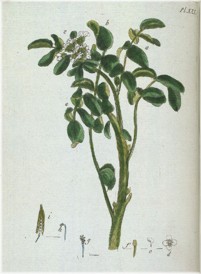

Image is from Recueil de plantes coloriees by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden Library.