Vanilla:

The Orchid of Flavors

By Audrey Stallsmith

Ah, you flavor everything; you are the vanilla of society."

Sydney Smith, Lady Holland's Memoirs

Although it is difficult for us to imagine life without vanilla and chocolate, most of the world had never heard of these flavorings until Cortez invaded Mexico in 1519.

He found the Aztec emperor, Montezuma, and his court enjoying a drink called xocolatl. This exotic beverage combined chocolate, vanilla, and honey. I'll save the chocolate for February (Valentine's Day) and concentrate instead on the orchid, Vanilla planifolia, which became part of the conquistador's booty.

Initially, Europeans only used the flavoring in conjunction with chocolate. But finally, in 1601, Queen Elizabeth's chemist, Hugh Morgan, suggested that vanilla be allowed to stand on its own. The rest, as they say, is history!

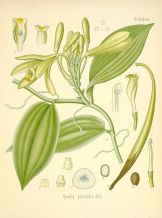

As with most orchids, the plant's greenish-yellow flowers grow in racemes, with the blooms opening one at a time. Each will fall off after a day if not pollinated. So the first attempts to grow the orchid outside of Mexico weren't worth beans!

Or, more accurately, they didn't produce any of the 6 to 10-inch seed pods which are called "beans." In 1836 a Belgian, Charles Morren, finally realized that only a tiny Mexican bee named Melipone was able to squeeze past the membrane separating the bloom's pistil and stamen to pollinate the plant.

After an ex-slave named Edmond Albius figured out a quick and easy method of artificial pollination in 1841, the Bourbon Islands off the southeast corner of Africa became the main exporter of the flavoring. The vanilla produced there is said to have a "darker," more "tonka-bean" flavor than the Mexican type.

True vanilla is the second most expensive flavoring in the world--after saffron--so imitations sprang up almost immediately. Originally they came from such unlikely sources as fir sapwood, asafoetida, oil of cloves, and coal tar. Today, however, most fake vanilla is produced synthetically. You can still find flecks of real vanilla bean in some premium ice creams. One taste will assure you that the original is still far superior to its imitators!

The vanilla orchid is a vining type, attaching itself to trees by means of aerial rootlets. Its name derives from the Spanish vainilla or "little sheath," while planifolia means "flat-leaved." Although there are other types of vanilla orchids, such as phaeantha, planifolia remains the most common. The Aztec name for vanilla, tlilxochitl, combines tlilli ("black") and xochitl ("pod").

The pods are originally green, however, and frosted with a vanillin substance called givre. When those pods begin to turn yellow, they are wrapped, steamed, then alternately dried and "sweated." Although we tend to associate the word "vanilla" with white delicacies, vanilla beans do actually turn black once the process of fermentation is completed. The extract is made by brewing chopped beans in an alcohol-water mix.

Vanilla beans need airtight storage to preserve their flavor. Some gourmets suggest burying those you want to keep in sugar.

Although some people attribute a sedative effect to vanilla and recommend it as a cure for hysteria, others insist that it "promotes wakefulness" and "increases muscular energy." Perhaps that is why it also has a reputation as an aphrodisiac!

According to Totonac mythology, Xanat, daughter of the Mexican fertility goddess (Centeotle?), transformed herself into the plant out of love for a Totonac youth. As the story goes, she wanted to provide "pleasure and happiness" to all humankind. Vanilla has certainly done that.

These days, the Totonacs employ the beans as air fresheners in their cars and linen closets. Here, in North America, we can add the sweet flavor to snow to produce our own premium desert.

To make snow ice cream, collect fresh, clean snow which has just fallen. Add milk, sugar, salt, and vanilla until you have achieved the right consistency and taste. Then, curl up in a cozy corner with your bowl and dream of tropical climes like Madagascar and southern Mexico where orchids quite literally grow on trees!

Vanilla planifolia image is from Kohler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden.