You Say Tomato

By Audrey Stallsmith

She went to the open door and stood in it and looked out among the tomato vines and jimpson weeds that constituted the garden.

Mark Twain, Tom Sawyer

There’s an old joke that we country people only lock our doors in late summer—and that’s to prevent our neighbors from unloading their excess garden produce on us! There’s some truth to that notion, since this is the time of year that we all have tomatoes piled high on our kitchen counters.

We’re not talking about those hard and scentless ethylene-ripened imposters you city dwellers buy in the supermarket, but the soft and sun-succulent real things! Considering how essential the tomato has become, it’s hard to believe that it didn’t gain popularity in the U. S. until the 1840’s.

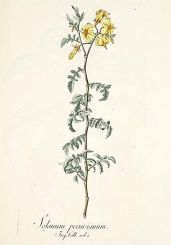

As with most of the solanums, the wild plant seems to have originated in the Andes of South America. From there, it spread northward to Mexico where the Aztecs domesticated the immigrant they called xitomatle. At that time, the fruits were small, round, and yellow—similar to our cherry tomatoes. The conquistadors apparently carried seeds with them back to Spain.

Matthiolus was the first European herbalist to mention the plant, calling it pome d’oro (“golden apple”). The French knew it as pomme d’amour ("the love apple"), but that may have been a mistaken translation of pome dei Moro ("Moor’s apple").

The tomato had to overcome the suspicion directed toward any member of the often toxic solanum family. Gerard wrote that “Apples of Love grow in Spaine, Italie, and such hot Countries” and added that persons from those regions “eate the Apples prepared and boiled with pepper, salt, and oyle.” He quickly added that the fruits “yeeld very little nourishment to the body, and the same naught and corrupt.”

He did grow the love apples in his own garden as an ornamental, however. By his day, the fruits had grown to “the bignesse of a goose egge or a large pippin.” Even the official name of the tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum, contains some of the old prejudice. It means “edible wolf peach”—a reference to the fact that witches were believed to use solanums to call up werewolves.

Although colonists carried tomato seeds back to the Americas, only a few adventurous cooks or gardeners—like Thomas Jefferson—actually consumed the fruits. Everybody else used them externally to remove pustles! George Washington Carver tried, without success, to talk his poor neighbors into growing tomatoes. The Creoles, perhaps because of their French heritage, were the first Americans to really adopt "love apples" into their diet.

There is a legend that, in 1820, a colonel proposed to consume a bushel of the fruits in front of the Boston courthouse. The story holds that an enthusiastic crowd gathered to watch him die, and found his failure to do so a bit anti-climatic! Whatever the truth of the matter, by the 1840’s the tomato was suddenly all the rage.

The enthusiasm has not abated since. The tomato is the most widely consumed vegetable (actually a fruit) in the U. S. Most of us eat about 13 pounds per year of fresh tomatoes and 20 pounds of the processed variety.

It’s a good thing too. Due to an antioxidant called lycopene, people who consume large amounts of tomatoes have a reduced risk of cancer. They also improve their heart health, since tomatoes help dissolve animal fats and, being high in potassium, lower blood pressure. The chlorine and sulfur in the fruits also detoxify the body and stimulate the liver. As the colonists knew, tomatoes applied to the skin will help draw pus from wounds. A mixture of tomatoes and buttermilk is also reputed to turn a sunburn into a tan.

Considering how many of the nightshades have now become respectable staples of the American diet—potatoes, eggplants, and peppers, to name a few—maybe we should be looking a little more closely at other members of this sprawling family. Granted, a few of them are really poisonous, but every clan is entitled to a few black sheep!

Lycopersicon peruvianum image is from Icones Plantarum Rariorum edited by Nicolao Josepho Jacquin, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden