Sassafras:

Spice of Spring

By Audrey Stallsmith

In the spring of the year when the blood is thick, there is nothing so fine as a sassafras stick.

Ozark ballad

Every year, at maple syrup time in late February, my father digs sassafras roots to brew a spring-tonic tea. In fact, he often simmers those roots in maple sap, instead of water, to impart a natural sweetness.

This is a very old custom in rural areas such as ours. Jethro Kloss recommended the herb as a blood-purifier and tonic for the digestive system. He also found it valuable for treating skin disease and kidney problems. His book, Back to Eden, does caution, however, that sassafras shouldn't be taken for more than a week at at time. (Pregnant women should not consume it at all.)

Since the modern version of that book has been revised, the warning may have been added after scientific studies concluded that safrole, the major chemical in sassafras, causes liver cancer in lab rats. As a result, in 1976, the sale of sassafras roots was banned.

It's still legal to dig your own, and sassafras does not seem to have done my father any harm. But, then, he only drinks it for a few days out of the year. Those who are more addicted to the beverage claim that alcohol causes greater harm to the liver than sassafras does.

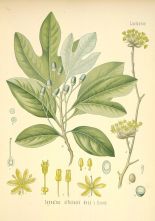

Originally called pauame by Native Americans, Sassafras officinale (or albidum) has also been known as ague-tree, black ash, cinnamon wood, file-gumbo or gumbo-file, smelling stick, golden elm, and saxifrax. "Sassafras" probably derives from the Spanish term for saxifrage. The tree can grow to sixty feet, but usually remains much smaller in the north.

This member of the laurel family is an oddity in that each tree is either male or female and can produce leaves in three different shapes. Those leaves, which--at 3 to 7 inches--are quite large, can be either simple, mitten-shaped, or tri-lobed (three-fingered). It's a shame that the tree is not used more often as an ornamental species, since it also boasts greenish-yellow flowers in the spring and deep blue olive-shaped drupes on red cups in the fall.

Those berries are very attractive to birds. The leaves are also inviting to the larva of such spectacular butterflies and moths as the spicebush swallowtail, luna, and promethea.

Sassafras does, however, spread very quickly, by underground runners, so it can become invasive. Since it prefers disturbed soil and the brighter light on the edges of forests, it coexisted quite comfortably with the early settlers.

The root was one of the most popular exports from the New World to the Old. In the Great Sassafras Hunts of 1602 and 1603, ships were dispatched to the "colonies" specifically to bring back more of the herb. Michael Drayton, in his poem "To the Virginian Voyage," speaks of the "cypress, pine, and useful sassafras."

British street-vendors added hot milk and sugar to the tea and hawked it from London street-corners as "saloop." At that time, strong-smelling plants were believed to have the most medicinal value. In Volpone, Ben Jonson mentions sassafras, along with tobacco, as one of the "Indian drugs."

A somewhat alarming concoction called Godfrey's Cordial was administered to children, to relieve colic or hunger pains. Along with sassafras, molasses, and caraway, this patent medicine reportedly contained both opium and brandy. We can only hope that the amounts of the latter two ingredients were small!

The spicy scent of sassafras may remind you of Hires or A & W--with good reason. The original root beer was made from fermented sassafras and molasses.

Down south, the dried leaves, known as file, still flavor condiments and thicken gumboes. This practice may have originated with African slaves who were accustomed to adding powdered baobab leaves to their soups. (File is legal, since sassafras leaves don't contain safrole.)

Because it resists decay, the wood was used for ships, fenceposts, and railroad ties. Country folks constructed beds from it, as well as chicken roosts, since the strong smell was believed to repel bugs and promote drowsiness. Perhaps that explains why, in Cooper's Last of the Mohicans, the ladies in the cave slept on sassafras boughs.

Those who don't want to run the risk of consuming sassafras might want to try spicewood (lindera benzoin) as an alternative. The flavor is very similar and, as far as I know, lindera has not been banned. But perhaps nobody has tried it on rats yet!

Sassafras albidum image is from Kohler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden.