Mum's the Word

By Audrey Stallsmith

Why should this flower delay so long

To show its tremulous plumes?

Now is the time of plaintive robin-song,

When flowers are in their tombs.

Through the slow summer, when the sun

Called to each frond and whorl

That all he could for flowers was being done,

Why did it not uncurl?

It must have felt that fervid call

Although it took no heed,

Waking but now, when leaves like corpses fall,

And saps all retrocede.

"The Last Chrysanthemum" by Thomas Hardy

The chyrsanthemum is one of the few outdoor flowers still blooming in November, and even it has usually begun to look a little tired by this point. But have no fear! Ever since florists learned how to force the mum into bloom whenever they wanted--by providing the equivalent of shorter daylight hours--this flower has also become the most widely grown container plant in the U. S.

But its popularity didn't begin here. The Chinese were cultivating the mum as early as the 15th century BC, and it made the move to Japan around the 8th century AD. It has always been "the" flower of the Orient. The Chinese listed it among their four noble plants-along with bamboo, plum, and orchid. And one of their philosophers advised, "If you would be happy for a lifetime, grow chrysanthemums."

The Japanese were no less smitten with the plant. They considered it a symbol of the sun, and made it the crest of their Emperor. They also celebrate a national chrysanthemum day known as the Festival of Happiness. Oddly enough, however, in some European nations the flower is associated with death and only used for the decoration of graves.

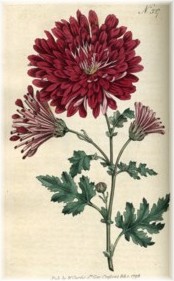

Its name derives from the Greek chrysos ("gold") and anthemon ("flower"), implying that the original species types were probably yellow. But a broad array of colors has been developed since, not to mention, a wide variety of types-with some of the more exotic being incurve, reflex, pompom, anemone, spoon, and quill.

The Chinese used all parts of the plant, boiling the roots to make a headache remedy, brewing the leaves into teas that are said to improve the eyesight, and eating the sprouts and petals in salads. Because it lowers blood pressure, chrysanthemum can relieve the headaches and dizziness often associated with that condition. It is also antibiotic and can help clear up infections as well as break fevers. The Japanese sometimes place a single petal in the bottom of a wine glass to wish themselves a long and healthy life.

Perhaps due to its ability to withstand cold and dark conditions, the Chinese chrysanthemum stands--in the Language of Flowers--for "cheerfulness under adversity." The meaning of other types depends on their color, with red representing "love," white "truth," and yellow "slighted love." And, understandably, because they lead the way into winter, in some cultures the mums stand for death.

But we can still be glad that all seasons, both of weather and life, have their glories. And that, as Oscar Wilde wrote in "Humanitad," "When the lingering rose hath shed/ Red leaf by leaf its folded panoply,/ And pansies close their purple-lidded eyes,/ Chrysanthemums from gilded argosy/ Unload their gaudy scentless merchandise."

I wouldn't call them scentless, however. To me they smell of crisp days, the pungent smell of burning leaves, football, cider, and the first snowfall. And they are a sure sign that adversity can sometimes bring out the best colors-not only in the fall landscape, but in ourselves.

Plant plate and background is by Sydenham Edwards from a 1796 copy of The Botanical Magazine.