Mad Mandrake

By Audrey Stallsmith

And shrieks like mandrakes torn out of the earth, That living mortals, hearing them, run mad. . .

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

The idea that mandrake would scream when uprooted, causing insanity or death to those hearing it, is only one of the strange superstitions ascribed to this herb. But some people believed the fable to the extent that they tried to teach dogs to harvest the roots for them!

"There hath beene many ridiculous tales brought up of this plant," sixteenth-century herbalist John Gerard wrote scornfully, "whether of old wives or some runnagate Surgeons and Physicke-mongers, I know not."

Most of those tales arose from the forked root's supposed resemblance to a human figure. "Whereas in truth," Gerard points out, "It is no otherwise than in the roots of carrots, parsneps, and such like. . ."

Still, mandragora, which actually means "hurtful to cattle," also acquired the sinister title of Satan's Apple. It may have earned that nickname because it belongs to the "shady" nightshade family. In small doses, it is a narcotic, and was once used as a sedative and pain-reliever. In Othello, Iago predicts that, "Not poppy nor mandragora,/ Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,/ Shall ever med'cine thee that that sweet sleep/ Which thou owedst yesterday."

In another of Shakespeare's plays, Cleopatra asks for mandragora, "that I might sleep out this great gap of time/ My Antony is away." And Coleridge wrote, "Into the land of dreams I long to go. Bid me forget! Mandragora."

Like most narcotics, however, the plant can also be poisonous-possibly causing delirium and madness before death. An old saying warns, "A small dose makes vain; a large dose makes an idiot."

Mandrake also rendered patients unconscious for surgery. Dioscorides wrote that it was given to "such as cannot sleep, or are grievously pained, and upon whom being cut or cauterized they make a not-feeling pain." It would cause the patient to be "sensible of nothing for three or four hours."

The herb treated depression and convulsions as well, and sedated the mad or demon-possessed. The leaves, boiled in milk, were applied as poultices. One writer claimed that mandrake "cures every infirmity--except only death where there is no help." But you definitely do not want to experiment with it at home, since its poison is believed to be similar to that of atropine (belladonna).

Another superstition which Gerard reports of mandrake is "that it is never or very seldome to be found growing naturally but under a gallowes, where the matter that hath fallen from the dead body hath given it the shape of a man." He rightly dismisses this belief as a "doltish dream."

Some of the more gullible, however, proved eager to purchase the roots as protective amulets called puppettes and mammettes. Unscrupulous merchants shaped bryony roots to look like mandrake, going so far as to add grains for eyes. In France, the dolls, considered elves and known as magloire, were sometimes consulted on important questions. But ownership of one might invite charges of witchcraft! In the Language of Flowers, mandrake stands for "horror" or "rarity."

In a flippant poem which speaks of impossibilities, Donne advises, "Go and catch a falling star,/ Get with child a mandrake root." Gerard added that there were besides "many fables of loving matters, too full of scurrilitie to set forth in print, which I forbeare to speak of." He probably meant mandrake's reputation as a "love apple" or charm.

The herb would supposedly end barrenness or sterility as well. The latter belief is actually mentioned in scripture (Genesis 30:14), but there is some doubt whether the mandrakes indicated were really mandragoras. Gerard points out that "yong Ruben brought home amiable and sweet-smelling floures (for so signifieth the Hebrew word. . .). Now in the floures of Mandrake, there is no such delectable or amiable smell."

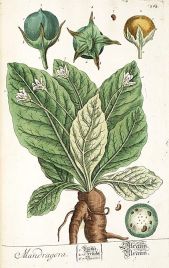

Mandrake has a crown of large, unpleasantly scented leaves and primrose-like white flowers tinged with purple. It is possible, however, that what Reuben gathered were the ripe yellow fruits, which boast an apple-like shape and scent and are reputed to be the only non-toxic part of the plant.

The danger is certainly real. As for the superstitions, we might do well to heed Gerard's advice. "All which dreams and old wives tales you shall from henceforth cast out of your books and memory. . .for I my selfe. . .have digged up, planted, and replanted very many, and yet never could either perceive shape of man or woman. . ."

Apparently he heard no screams either! But this plant can reinforce the old fairy-tale lesson that it is possible to find golden apples in the most unlikely places.

Mandragora officinalis image is from Herbarium Blackwellianum, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden.