Frilly Fuchsia

By Audrey Stallsmith

"Now, just look at that fuchsia!" she exclaimed, pointing.

"H'm!" He made a curious, interested sound. "You'd think every second as the flowers was going to fall off, they hang so big an' heavy."

"And such an abundance!" she cried.

"And the way they drop downwards with their threads and knots!"

"Yes!" she exclaimed. "Lovely!"

Sons and Lovers, D. H. Lawrence

With its bright colors and flounced “skirts,” fuchsia might be said to be the ultimate feminine bloom. Its flowers, in fact, are frequently referred to—in jewelry terms--as “eardrops.” Of course, many of the frills are the result of hybridizing, since species types of the plant tend to be more austere.

The fuchsia was first mentioned in Father Carolo (Charles) Plumier’s Nova Plantarum Americanarum Genera, published in 1703. A French Jesuit monk who served as Louis XIV’s botanical emissary to Latin America, Plumier named at least 50 different genera, most after other famous plant lovers.

Ignoring the fuchsia’s native moniker, thilco, he named it for German botanist, Dr. Leonhart Fuchs. (Among the other flowers Plumier dubbed were begonia—after botanical patron and Canadian governor Michel Begon—and lobelia—after Flemish botanist Mathias de L’Obel.)

Most fuchsias originated in the mountain forests of South and Central America, though three came from New Zealand (excorticata, perscandens, and procumbens) and one from Tahiti (cyrtandroides). As a result, they generally prefer cool conditions, filtered light, and damp but well-drained soil.

Fuchsia coccinea reached England in the late 1700’s. Kew Gardens records a plant donated by a Captain Firth, who brought it from Brazil. It was first marketed commercially by nurseryman James Lee, who asked and got an outrageous price for the newcomer. This was, of course, before people realized how easy it is to propagate fuchsias. (Most cuttings of the plant will root readily and quickly in water.)

With its unusual dangling blooms and vivid hues, the flower became an instant success. By the Victorian era, when it reached its peak of popularity, there were at least 1,500 cultivars available. The Victorians were the first to take to “houseplants” in a big way and the fuchsia, with its preference for cool temperatures and lower light conditions, proved ideal.

Although generally grown as an annual these days, it will last indefinitely if protected from freezing temperatures, and will even make a gnarly tree for bonsai. It came to stand for “taste”—presumably good taste—in the Language of Flowers. (Though the fruits of some fuchsias, such as splendens, are said to be edible.)

Since the plant dislikes extreme light, heat, and/or arid conditions, it will usually flourish where it receives some morning or evening sun but avoids the most scorching midday rays. Like most ladies, this one will look her soignee best if allowed to “keep her cool”!

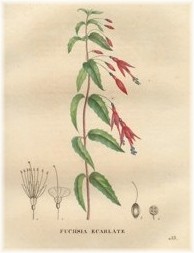

Plant plate is from La Flore et la Pomone Françaises, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden Library