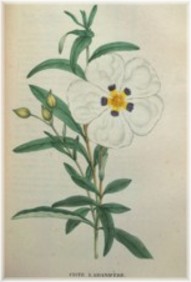

Redolent Rockrose

by Audrey Stallsmith

Heap cassia, sandal-buds and stripes

Of labdanum, and aloe-balls,

Smear’d with dull nard an Indian wipes

From out her hair: such balsam falls

Down sea-side mountain pedestals,

From tree-tops where tired winds are fain,

Spent with the vast and howling main,

To treasure half their island-gain.

“Song from Paracelsus” by Robert Browning

Cistus is one of those flowers whose photos I salivate over, but I know it would never survive in Pennsylvania’s cold clay soil. I did have a plant of Cistus ladaniferus, which I grew from seed, kept in a pot, and faithfully brought indoors every winter for a few years. Although it survived under the grow-lights, it never bloomed. And, when I tried to transplant it into a larger pot, it promptly expired!

I have had a little better luck with the plant’s lower-growing and hardier relative, Helianthemum, which derives its name from the Greek for helios (“the sun”) and anthemum (“a flower”). But even it doesn’t hold up well here unless planted in very well-drained soil.

One wild type, Helianthemum canadense, is also known as frostweed for the peculiar way in which curved ice crystals protrude from near the roots of the plant in winter. (Possibly sap bursts from the stems and freezes.) Both cistus and helianthemum are more commonly known as rockrose.

Cistus originated in the Mediterraenean region where it flourishes in sandy soil and exudes the fragrant and sticky ladanum or labdanum for which it is famous. At one time that resin was reportedly harvested from the hair of grazing animals which had brushed against the plants. In fact, those patently false beards worn by some Pharaohs may have been goat hair oiled with labdanum (perhaps the origin of the word “goatee”).

Biblical scholars believe that some references to myrrh—and possibly even onycha—actually referred to ladanum. It is considered similar to the prized—and now forbidden—ambergris derived from sperm whales.

Although an evergreen, cistus is only hardy in zone 7 and up. In addition to its use as a perfume, it has long been employed to increase immunity to disease, to kill bacteria and fungi, and to treat colds, rheumatism, and menstrual problems. (Perhaps that is what won it the “popular favor” awarded to it in the Victorian Language of Flowers.) Modern science has discovered that the plant is rich in polyphenols and may actually kill cancer cells.

In The Fragrant Path, Louise Beebe Wilder describes Cistus ladaniferus as having flowers with the “shape of little single roses, white with a purple-red spot at the base of each petal. She also quotes Sir Herbert Maxwell on the evanescent nature of the blooms. In his Flowers, he writes, “In Andalusia where some of the hillsides are white for miles with the bloom of cistus ladaniferus, they are brown by four o’clock afternoon, but under each bush is spread a yellow carpet of fallen leaves.”

Plant plate and background is from Traité des arbrisseaux et des arbustes cultivés en France et en pleine Volume 1, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden Library.