Castigated Castor Bean

By Audrey Stallsmith

In the good old days of a generation ago, the measure of the efficacy of any remedy was its nastiness. . .Of all the villainous abominations thus held by our elders to be “good”. . .none could hold a candle to castor oil. . .whose very name calls up memories of horror that are as lasting as life itself. . ..

The National Druggist, Volume XXV, 1895

As indicated by the quote above, castor oil has been widely employed as a laxative throughout history—and as widely hated! Although it is considered safe, I’m guessing that an oil pressed from toxic seeds probably derives its purging action from that toxicity. Nevertheless, it apparently didn’t kill the schoolchildren who once found it the bane of their existence.

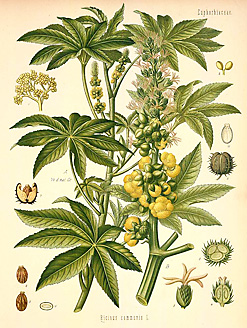

Fortunately, the plant from which the oil is derived is more attractive than its product. The castor bean (Ricinus communis) can shoot up 15 feet in a single season and may have been the fast-growing “vine” which shaded Jonah in scripture.

Its beans are the source of the deadly poison known as ricin, as well as of the aforementioned oil, which also has been burned in lamps, added to soap, and used externally to soothe skin ailments. (Keep in mind, though, that castor bean foliage and seeds may irritate the skin of some people.)

Native to northeast Africa and the Middle East and sometimes called Palma Christi (“palm of Christ”) due to its lobed leaves, the plant can grow into a 40-foot tree in USDA zones 9 and up. Once known erroneously in Jamaica as Agnus castus, it probably derived its “castor” from that name.

In colder climates, it generally is employed as an ornamental annual. Although castor bean’s small yellow-green flowers aren’t showy, it’s foliage is--especially that of the red or purple cultivars—and its thorny round seedpods are highly decorative as well.

I received a few seeds in a Secret Santa Swap last year, most of which had gotten crushed en route. (Yes, I handled those crushed seeds very carefully!) Not having room for the plants myself, I gave the few whole beans to my mother, who had grown other castor beans in her large vegetable garden before.

This cultivar, which shot up to at least eight feet tall over the course of the summer, turned out to have handsome maroon foliage and prickly round seed pods of the same color. As I harvested a few of those pods recently, I wondered whether their thorns could inject ricin into my system. I concluded that wasn’t likely or there would be a lot more gardeners who didn’t survive into old age! Besides, if the Internet sources I consulted are correct, the poison is found inside the beans--not on the outside of their pods.

Gardeners with young children probably will want to think twice about growing this plant—or pinch off those pods before they fully form. (Because a single plant produces both male and female flowers, castor beans are self pollinating.) Although the seeds derived their Latin name, Ricinus, from the fact that they resemble dog ticks, they also resemble edible beans, so children might be tempted to sample them.

May Folwell Hosington once asked, in a poem titled "Greatness," "If a man is wealthy enough, will he then own God?/ Will the castor bean wax into sweet sugar cane?/ Will an ass fetch the price of a horse, though he spurn the sod/ And run as swift a race on the grassy plain?"

Although the answer to all of those questions is "definitely not!" the castor bean has its place in the grand scheme of things and can be a blessing. Provided, of course, that you don't try to eat it!

The Ricinis communis image is from Kohler's Medizinal Pflanzen, courtesy of plantillustrations.org.