Bouncing Bogberries:

Cranberries and Blueberries

By Audrey Stallsmith

Your nose is as red as that cranberry sauce," answered Fan.

Louisa M. Alcott, Old-Fashioned Girl

Where fires thou find'st unraked and hearths unswept,

There pinch the maids as blue as bilberry.

William Shakespeare, The Merry Wives of Windsor

One of the joys of Thanksgiving is successfully plopping jellied cranberry sauce, whole, out of the can onto the serving plate. Tradition holds that cranberries were eaten at the first Thanksgiving in 1621, though probably not in such quivery form!

Although the eastern Indian tribes knew the fruit as sassamanesh or ibini ("bitter berry"), the Pilgrims dubbed it "craneberry," the blossom being thought to resemble the head of that particular bird. Cranberries did not become a popular part of the holiday feast, however, until Grant had them served to his troops in 1864--just a year after Lincoln proclaimed Thanksgiving an official national holiday. Apparently the soldiers liked the piquant flavor. Sailors did too, since the berries prevented scurvy on long voyages.

Cranberries were sometimes also known as "bounce-berries," because good ones will bounce, while rotton or damaged ones won't. This was supposedly discovered by a gentleman who kept his in his loft and had to pour them down the stairs! Cranberries are still sorted by bounceboard separators.

There are only three fruits native to America, and two of them--cranberry and blueberry--belong to the Vaccinium family. Native Americans made good use of both, pounding the dried berries with jerky and suet to form pemmican cakes and dying their robes in cranberry or blueberry hues.

The two vaccinium "brothers" are at home in the acidic, damp, but well-drained soil near swamps. (Commercial cranberry bogs are flooded only at harvest-time and during the winter.)

I vividly remember picking wild blueberries as a child. We kids would belt plastic milk pitchers to our waists to leave both hands free for stripping the succulent fruits from their bushes. Since the wild berries are much smaller (and darker) than the domestic types, gathering them took time.

We would inevitably eat half of our harvest and complain loudly, through blue-stained lips, about the mosquitoes whining around our heads. A sibling who found a good bush would, however, fall suspiciously silent--not wanting to share his or her bounty!

Although North America is the major exporter of both cranberries and blueberries, some wild varieties such as the ligonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) and the bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) grow in Europe too. The bilberry is also known as whortleberry, whinberry, trackleberry, or "hurts." Perhaps the latter name is a reference to the fruit's bruise-like color. The author of Wuthering Heights mentions bilberries climbing over the churchyard wall from the moor. Whinberry, in fact, means "furzeberry."

Almost everyone has heard that cranberry juice, if consumed often enough, will stop bladder infections. It is also said to break up kidney stones and deoderize urine. The modern consensus seems to be that the fruit's tannins prevent bacteria from adhering to body tissues, so the juice may ward off gum disease and ulcers as well. Blueberry reportedly has the same antibacterial effect, but isn't as readily available year-round.

The fruits of both vacciniums are very high in the antioxidants and flavanoids that fight cancer and heart disease. Those berries may also prevent cataracts, repel viruses, and cure diarrhea.

If you have any whole cranberries left over from Thanksgiving, you might want to try stringing and drying them to make decorative red "chains" for Christmas. They will stain your hands, but that's all part of the fun.

Cranberries and blueberries can also color our memories with the anticipations of childhood. Wading through the July weeds or clustered eagerly in the kitchen on a certain morning in November, we kids never doubted that abundance was very close and only waiting to be discovered!

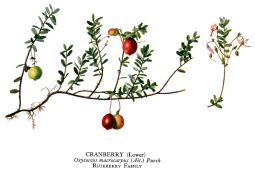

Vaccinum myrtillus image is from Bilder ur Nordens by Carl Lindman, courtesy of the TAMU Vascular Plant Image Library and oxycoccos macrocapnos image by the National Geographic Society, courtesy of the Southwest School of Botanical Medicine.