Petrifying Poison Ivy

By Audrey Stallsmith

Ye who are kicking against Fate,

Tell me how it is that on this hill-side,

Running down to the river,

Which fronts the sun and the south-wind,

This plant draws from the air and soil

Poison and becomes poison ivy?

"Calvin Campbell" by Edgar Lee Masters

Just in time for Halloween, I'm going to bring up one of the scariest plants known to man. There's nothing like the horror of taking a Sunday saunter, innocent as a babe in the woods, only to look down and discover you're ankle deep in leaves-of-three. Instead of seeing your past life flash before your eyes, you're more likely to feel your blood run cold as you envision your itchy, irritable future.

Although there are a lot of other P words we can fling at this ivy--perverse, pernicious, pestilent--its R-rich Latin name indicates why it will always get the upper hand. Rhus radicans can be interpreted simply as a plant "having rooting stems." That means the creepy crawler can attach itself to whatever it darn well pleases.

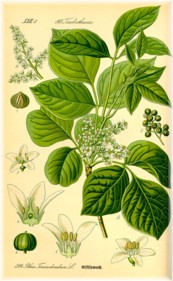

And, as Pamela Jones points out ominously in Just Weeds, the villain has many guises. "Each leaf consists of three leaflets attached to a single leaf stem. . .Unfortunately, recognition is often frustrated by the variations to be found in those leaflets. They may be smooth edged, lobed, or toothed, glossy or dull, dark or pale green, slightly hairy or hairless."

That explains why you can contract the rash without realizing you've ever been near the plant. Even people like me, who supposedly "don't get poison ivy," are scared to death of it. We know our immunity isn't guaranteed to last forever.

As its name indicates, Rhus radicans is a sumac. (Rhus derives from the Greek rhodus or "red.") It was once known as Rhus toxicodendron, which is where the "poison" comes in! Poison oak or Rhus diversiloba--which we can assume is diversely lobed--is a more western type of the plant. Since it's a New World species, poison ivy was an unpleasant surprise to the original settlers. Though we have since generously shared it with other parts of the world!)

In 1609, Captain John Smith noted that: "The poisoned weed is much in shape like our English ivy, but being touched, causeth redness, itching, and lastly, blisters, and which, howsoever after a while pass away of themselves, without further harm; yet because for the time they are somewhat painfill, it hath got itself an ill name, although questionless of no ill nature."

The hairy brown vine can grow almost anywhere, but seems to prefer partial shade. It produces clusters of small off-white flowers in June, which are followed by gray berries. Poison ivy's resinous juice turns black when exposed to air and is infected with a substance called urushiol.

That substance, according to James Duke's The Green Pharmacy "does its dirty work by binding to skin cells and triggering the rash-producing irritation. A mere one-billionth of a gram of urushiol is enough to affect those who are highly sensitive."

Duke should know, since he credits poison ivy for his decision to become a botanist. "One time, long ago when I was a kid, I. . .unknowingly used poison ivy as toilet paper. I got a bad rash in a bad spot, and it tormented me for more than a week. To avoid a repeat of that experience, I figured it would serve me well to learn how to recognize poisonous plants."

We country kids were always warned to wash ourselves with a strong alkaline laundry soap such as Fels-Naphtha, if we felt we'd come in contact with poison ivy. The other most popular antidote is the wild impatiens known as jewelweed. (Also called touch-me-not or snapweed, this rescuer grows in semi-shady places too. The orange flowered type is officially known as Impatiens capensis or biflora and the yellow has been dubbed Impatiens pallida.)

Duke espouses jewelweed himself, saying he rubs all of his exposed skin with the crushed plant before he has to handle poison ivy. He reports his friend, Robert Rosen, "may have come up with an explanation for jewelweed's effectiveness. . .Dr. Rosen has identified the active ingredient in jewelweed as a chemical called lawsone. This substance binds to the same molecular sites on the skin as urushiol. If applied quickly after contact with a poisonous plant, lawsone beats the urushiol to those sites, in effect locking it out."

If it's too late for jewelweed, Heinerman's Encyclopedia of Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs recommends any of the following as a soother for your rash: acorn infusion, aloe vera, cornstarch, goldenseal infusion, watermelon pulp, or an infusion combining okra, slippery elm bark, and white oak bark.

Believe it or not, poison ivy does have its uses. It has been employed to treat other types of skin eruptions, such as herpes, as well as incontinence, palsy, paralysis, and rheumatism. And that dark juice makes a nice indelible ink or shoe polish-presuming you can come up with some way to detoxify it!

The plant is actually quite pretty this time of year, when its leaves turn an enticing red. I was curious to see what it stood for in the Language of Flowers, but it wasn't included. I can see why. Although it might be tempting to send your enemy a Rhus radicans bouquet, this is one circumstance where malice can quite literally hurt the sender as much as the receiver!

Poison ivy, rather than its antidote, is probably the plant that should be called touch-me-not. So, when you're out admiring the fall colors, you'd do best to heed an old warning. "Leaves of three; let them be!"

Image is from Flora von Deutschland Österreich und der Schweiz by Otto Wilhelm Thome, courtesy of The Digital Flora of Texas Vascular Plant Image Library.