Snappy Impatiens

by Audrey Stallsmith

I could bring you jewels, had I a mind to,

But you have enough of those.

I could bring you odors from St. Domingo,

Colors from Vera Cruz.

Berries of Bahamas have I,

But this little blaze--

Flickering to itself in the meadow--

Suits me more than those.

Never a fellow matched this topaz

And his emerald swing,

Dower itself for Bobadilla.

Better--could I bring?

Emily Dickinson

Back when we farm kids poked jewelweed pods for the fun of seeing them pop, we never suspected that the wildflower-with its spring-loaded method of seed dispersal-was a relative of one of the most popular bedding annuals in the world. The pods' hair-triggers explain both the plant's Latin title, which derives from "impatient," and nicknames like "touch-me-not" and "quick-in-the-hand."

The "jewel" part refers to the glittery raindrops that roll around like mercury on the wildflower's water-resistant leaves. Impatiens pallida, with its blond blooms, is called yellow jewelweed. And Impatiens capensis, with its ruddier freckled cheeks, is better known as spotted jewelweed.

These plants' reputation for preventing or relieving poison ivy rashes is dismissed as "folklore" by some. But Dr. James Duke, author of The Green Pharmacy, frequently proves the point to his students by rubbing poison ivy on both wrists, and then treating only one with jewelweed. He reports that, three days later, "the wrist rubbed with jewelweed invariably shows much less of a rash, and sometimes none at all."

He notes that a chemist named Robert Rosen has found an explanation. The lawsone in the wild impatiens binds to skin cells more quickly than does the urushiol in poison ivy, "locking out" the latter. Duke also recommends jewelweed for the treatment of hives, especially those caused by stinging nettles.

Jewelweed should only be used for external applications, however, since calcium oxalate crystals render its foliage somewhat toxic. It can cause vomiting and diarrhea, if consumed. But Native Americans did sometimes eat the greens after boiling them several times over to remove the poison.

With the exception of the jewelweeds, most impatiens originated in the mountains of Asia and Africa, where some were "discovered" by doctors or missionaries. One of those physicians, Dr. John Kirk, originally proved his mettle by sticking with David Livingstone through thick and thin.

But the greatest test of his perseverance probably occurred when a couple cases of plant specimens that he had carefully gathered on his travels were lost on their way back to England. Fortunately, this calamity doesn't seem to have dampened Kirk's interest in botany. After he became Consul General for Zanzibar, he is credited with introducing Impatiens sultani--named in honor of the sultan of Zanzibar--to the rest of the world

This plant is also known as impatiens walleriana after British missionary Horace Waller, also a friend of Livingstone. With its gangly three-foot growth and inconspicuous blooms, walleriana wasn't exactly the belle of the ball. But plant breeders like Bob Reiman and Claude Hope saw this "wallflower's" potential.

Reiman is credited with giving the plant a more compact growth and larger flowers, while Hope developed a broader palette of colors. In 1968, Hope introduced the Elfin series of impatiens to the gardening market. The rest, as they say, is history! Easy to grow and one of the few plants that can flower prolifically in shade, Busy Lizzie proved irresistible.

In 1970 the members of a plant-collecting trip, conducted jointly by Longwood Gardens and the USDA, brought Impatiens hawkeri back from New Guinea. The plant was crossed with other types from Java and the Celebes Islands to produce Circus--the first series of New Guinea impatiens--in 1972.

Knowing a sure thing when they see it, seed companies keep coming up with more Lizzies. The hooded flowers of the new African Orchid varieties are actually somewhat similar to those of jewelweed, and even to orchids as the name indicates. They reportedly derive from a cross between Impatiens auricoma and tuberosa. Auricoma has also been mated with walleriana to produce the new Seashell and Fusion types.

Although a favorite of amateur gardeners, impatiens are often disparaged by the more advanced who affect to find something artificial in all that blooming. I, however, am among the Philistines who want all the flowers I can get--especially at this time of year, when snow covers the ground outside. And the easy-going impatiens are among the few plants that will condescend to bloom indoors under unfavorable conditions. They are also easy to propagate, since cuttings from most will root quickly in water.

Impatiens really should appeal to plant connoisseurs too, since there are scads of species types out there that remain obscure enough to suit even the most discriminating gardener. For more information, consult Raymond Morgan's excellent new book, Impatiens: The Vibrant World of Busy Lizzies, Balsams, and Touch-me-nots.

Although I've managed to accumulate a few of the species types, like grandis, hians, niamniamensis, etc., I'll continue to cultivate the more common walleriana hybrids too-for the same reason that I continue to grow petunias. The combination of good looks and good nature is hard to find. So, when you come across a plant like impatiens which is generous with both, you'd be well advised to hang on to it!

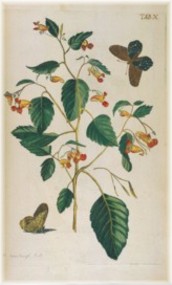

Plant plate and background is from Afbeeldingen van Zeldzaame Gewassen, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden Library.