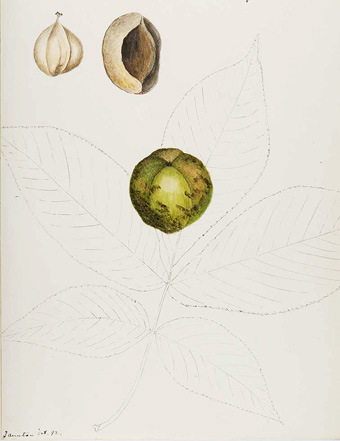

Homespun Hickory Nut

By Audrey Stallsmith

Lincoln, six feet one in his stocking feet,

The lank man, knotty and tough as a hickory rail,

Whose hands were always too big for white-kid gloves,

Whose wit was a coonskin sack of dry, tall tales. . .

“John Brown’s Body” by Stephen Vincent Benet

We noticed that a heavy crop of nuts already is weighing down a roadside hickory this year. Old-timers probably would take that to presage a bad winter, in which the squirrels will need a plentiful stash of supplies to survive. But hickories have a reputation for producing a bumper crop only every third year, so this could just be the magic year for this particular tree.

I remember how we used to enjoy gathering those nuts as children from the shagbark hickories in our pasture. Clad in fascinating “fringe,” those tall trees dropped leathery green balls, just beginning to brown and split open in neat sections.

Children always love unwrapping presents, so we would sit amidst dead leaves, stripping off the sections to reveal the hard, almost white nuts beneath. Cracking those generally was an adult task, as it required a hammer--and thus could result in smashed fingers rather than shells if not handled carefully.

Although not the most sophisticated member of the Carya family, the hickory nut has a flavor to rival that of its walnut and pecan kin. The shagbark type (Carya ovata) generally is considered to have the best taste, though it doesn’t begin blooming until it is about 20 years old or “shagging” until it is 25, and generally only hits its nut-bearing prime at about 40. Bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis) nuts reportedly are inedible while the pignut type (Carya glabra) are popular with hogs. Mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa) may provide the best wood for smoking hams from those hogs.

There’s a reason that hickory nuts seldom appear in supermarkets, that being the difficulty of extracting them from the shell. Back in the pre-TV or Internet days, country folk often worked on prying out those kernels for their Christmas fudge, once they didn’t have much else to occupy them during long winter evenings.

Powhatan Native Americans used to grind up the kernels and boil them to extract a white liquid they called pawcohiccora or pokahichary, probably their version of vegetable oil. That eventually was corrupted into just “hickory” by white colonists, who called the liquid "hickory milk." It’s also possible to make a syrup by shredding the tree’s inner bark and cooking it under pressure.

As mentioned in the poem fragment about Lincoln at the head of this article, hickory wood is tough and probably explains why Andrew Jackson was known as “Old Hickory.” The resilience of that wood has long made it popular for handles, bows, cask hoops, and switches with which to discipline erring children. So “a dose of hickory tea” didn’t actually mean tea!

Speaking of such beverages, Mark Twain writes in Tom Sawyer that “Huck found a spring of clear cold water close by, and the boys made cups of broad oak or hickory leaves, and felt that water, sweetened with such a wildwood charm as that, would be a good enough substitute for coffee.” Although Lincoln also had wildwood charm, his resilience proved more important. Like the hickory, he, too, was gangly, craggy, and able to take pressure without cracking under it.

The watercolor sketch of hickory is by Helen Sharp, courtesy of plantillustrations.org.