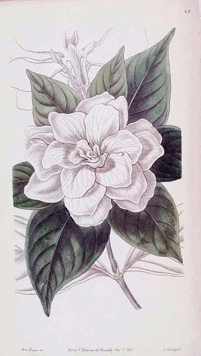

Glamorous Gardenia

By Audrey Stallsmith

You can be. . . in white satin, with gardenias in your hair and no sugar cane for miles, but you can still be working on a plantation.

Billie Holiday

Many a glossy-leaved and bud-filled gardenia plant has lured an unsuspecting customer into purchasing it. Once you get it home, however, those buds often start falling like hail.

Although greenhouse growers or southern gardeners generally can provide all the bright light, high humidity, and consistently mild temperatures the plant requires, most of us northern houseplant enthusiasts can’t. And any drastic change in its conditions may cause a gardenia to throw a temperamental fit.

That isn’t always the case, of course. This capricious southern belle may take a liking to some people. A woman for whom I once worked had a beautiful specimen growing in a south window with a sheer curtain between it and the sun. It was the exception to the rule. As Tovah Martin warns in The Essence of Paradise, “Look before you leap. Many courageous and capable gardeners have tried and failed with gardenias.”

That doesn’t mean the plants will die. Mine have usually survived while looking less than happy. I even had one produce a few blooms for me one summer when all my houseplants were outdoors, but nowhere near the number that greenhouse or in-ground specimens can manage.

The history of this flower is a bit tricky as well. The most common type, Gardenia jasminoides “Veitchii” or "Fortuniana" was supposedly discovered in China by plant explorer Robert Fortune in the mid-1800s. The gardenia had already been named by Linnaeus in the 1700s, however, in honor of a doctor and amateur botanist named Alexander Garden who owned an indigo plantation in South Carolina. Presumably then, another type was introduced to the western world earlier. It’s also a possibility that the original specimens sulked and died—which seems quite consistent with gardenia’s nature!—so that the plant had to be rediscovered.

It was called the cape jasmine, due to someone’s mistaken impression that it came from South Africa rather than Asia. The nickname stuck, even though the plant isn’t a jasmine either. The flower was a favorite of Billie Holiday and many other performers during the jazz age, as its glossy, double white blooms go well with tuxes and evening gowns.

Some modern gardenia cultivars that grow where the plant is hardy—USDA zones 8 to 11—can produce flowers up to 5 inches across. Potted houseplants probably won’t manage blooms larger than 3 inches.

Those blooms do have a strong scent, which probably explains the early reference to jasmine. The fragrance is loved by some gardeners, but not so much by others. Tovah Martin notes tersely that, “A gardenia is a heavy burden for any nose to bear.”

If you want to give your indoor gardenia its best chance at survival, pot it in acidic soil and irrigate it with rainwater rather than tap water, which can be too alkaline. Mist the plant frequently with rainwater as well, and position it where it gets very bright but filtered light, with daytime temperatures in the 70s Fahrenheit, and nighttime temperatures in the 60s.

In The Language of Flowers the bloom stands for “You are lovely” or indicates a secret love. We can imagine the gardenia, like other spoiled beauties, taking either of those compliments as only her due!

Gardenia jasminoides "Fortuniana" image by Miss Drake is from an 1846 edition of Edward's Botanical Register, courtesy of plantillustrations.org.