Amazing Maize

By Audrey Stallsmith

See, in arriere, the wigwam, the trail, the hunter's hut, the flatboat, the maize-leaf, the claim, the rude fence, and the backwoods village.

Walt Whitman--"Leaves of Grass"

Since the plant we call "corn" originated here in the Americas, it is just another example of how deprived the European diet was before the discovery of the New World! Although the word "corn" was already part of the international vocabulary, it generally referred to the most popular grain crop in any given country. In England that was wheat, in Scotland and Ireland, oats, and, in the Middle East, it may well have been barley.

When Columbus introduced "Indian corn" into Europe, it caught on fast and eventually became the second most-grown grain in the world. To differentiate it from their own corn, most Europeans still refer to the American type as maize, a word derived from the Arawak Indian "ma-hiz."

Maize originated as a wild grass in Mexico thousands of years ago. It is believed that, at the beginning, each individual kernel was encased in a husk, like wheat or oats. The ears we know today must have resulted from centuries of careful selection.

As we all know, the Pilgrims probably wouldn't have survived their first winters in this country without Squanto's advice on how to grow the New World grain. To Native Americans, corn, squash, and beans were Three Sisters, meant to be planted together. The first member of that trio remains our nation's most-grown agricultural crop today.

Apparently not all of our "corny" American customs caught on in Europe, however. When my German pen pal visited us one summer, she looked acutely surprised when we all started champing sweet corn kernels directly off the cobs. Once she tried this messy form of maize, she loved it too. But she reported afterwards that she could never find corn-on-the-cob in her own country.

Unfortunately, most Americans probably haven't experienced the real thing either. The imposter called "sweet corn" in supermarkets is generally much too mature, not to mention stale, and has lost most of its natural goodness.

The cobs should be picked while the kernels are still young and tender, and cooked and served within minutes of that harvesting. When our sweet corn is ready in August, we generally have it for supper every night. It's the only way we can keep up! Of course, by that time, we're usually trying to eat our way through a mountain of tomatoes and other vegetables too.

British herbalist John Gerard doesn't know what he missed! In his 1597 Herball he reported of the grain he called "Turky wheat" that "wee have as yet no certaine proofe or experience concerning the vertues of this kinde of Corne; although the barbarous Indians, which know no better, are constrained to make a vertue of necessitie, and thinke it a good food: whereas we may easily judge, that it nourisheth but little, and is of hard and evill digestion, a more convenient food for swine than for man."

We can forgive him for this opinion since his experience was probably with flint corn, which is even harder than our modern field corn. Sweet corn was apparently a mutation that didn't appear until 1779, and didn't become popular until the middle of the following century.

Our modern field or "dent" corn is a cross between flint and flour corn, the latter being a much softer and more easily ground variety. So field corn makes excellent corn meal, not to mention corn flakes, corn oil, cornstarch, corn syrup, corn liquor, etc.

Farmers also chop the green stalks for ensilage to feed their cattle during the winter months. Ensilage derives its name from the fact that it used to be stored in silos, but is more commonly crammed into "silo bags" these days. (It can also be made from chopped grass.) By late winter, this stuff really reeks, but the cattle don't seem to mind! The majority of the corn crop raised in this country is still fed to livestock, in one form or another.

Corn silk, although it looks purely decorative, contains the "female" pistils that catch the pollen from the "male" tassel to produce kernels. Tea brewed from corn silk is popular with the Amish as a tonic and is also, according to Jethro Kloss, "one of the best remedies for kidney, bladder, and prostate troubles." A diuretic, it increases urination to remove excess fluid from the body.

Corn husks are still used to make dolls and corn cobs to make pipes. At one time, Native Americans also constructed masks, mats, and moccasins from those shucks.

Most of us are still much more interested in the succulent kernels, though. But, while we are juggling steaming ears and calling on somebody to pass the butter, there are some debts we should recall. Besides saving our Pilgrim ancestors from starvation, Native Americans turned mere grass into a giant that could feed the world.

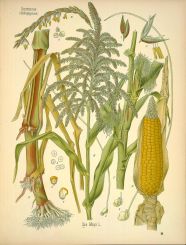

Zea mays image is from Kohler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden